BY NORVIN EITZEN

Forward

As I sit down to share the story of the Eitzen name, I’m filled with a deep sense of pride and gratitude for the journey that has brought my family to where we are today. This article, Tracing the Eitzen Legacy, chronicles the remarkable odyssey of my particular Eitzen family, whose roots stretch back to Northern Germany and the ancient Frisian lands, and who, over the course of several hundred years, found their way to the heart of Paraguay. From the windswept coasts of Friesland to the marshy Vistula Delta, the steppes of the Russian Empire, and eventually the arid Chaco of Colonia Fernheim, our story is one of resilience, faith, and an unwavering commitment to community—a testament to the enduring spirit of our Frisian Mennonite heritage.

I recognize that the Eitzen name is shared by many families, each with their own unique stories of migration, struggle, and triumph. This narrative, however, follows the specific path of my ancestors, beginning with their origins among the repopulated Frisians of Northern Germany and tracing their steps through centuries of upheaval and relocation. It captures how my grandparents, Jakob Eitzen and Maria Wiens, fled persecution in the Soviet Union, journeyed across Russia to China, and eventually settled in Paraguay, where they built a new life in Colonia Fernheim. While other Eitzen families may have taken different routes—some perhaps settling in North America or elsewhere—this account focuses on how we arrived where we did, preserving our faith and identity along the way.

The information in these pages was gathered over the course of several years, pieced together through family records, historical archives, and the invaluable resources of Mennonite genealogical databases like GRANDMA. It has been a labor of love, driven by a desire to understand the forces that shaped my family’s history and to honor the sacrifices of those who came before me. As you, the reader, embark on this journey through time, I hope you find joy in learning a little more about the Eitzen name and the remarkable path my family took across continents and centuries. May this story inspire you to explore your own roots, uncovering the legacies that have shaped your own family’s place in the world.

The Patronymic Origins of the Name "Eitzen"

The surname Eitzen, carried by my family through centuries of migration, is a window into the cultural and linguistic traditions of Friesland, Netherlands, where it first took root. Eitzen is a patronymic name, a common practice in Frisian society before the 19th century, derived from the given name Eite—a traditional Frisian name possibly meaning “wealth” or “protection,” rooted in Old Frisian or Germanic origins. The suffix -zen, a Frisian variant of the Dutch -sen, translates to “son of,” making Eitzen literally “son of Eite.” This naming convention was widespread in Friesland, where a person might be known as, for example, Jan Eitzen—Jan, son of Eite—reflecting their paternal lineage in a society that valued familial ties and community identity.

In medieval Friesland, patronymic names like Eitzen were more than identifiers; they were a cultural cornerstone, emphasizing lineage and belonging in a region known for its communal governance and independence, often referred to as the “Frisian Freedom.” Unlike feudal societies with rigid hierarchies, Frisians organized themselves into self-governing communities, and names like Eitzen reinforced the importance of family within these tight-knit groups. The use of patronymics also reflected the Frisians’ practical, oral tradition, where genealogies were passed down through storytelling, ensuring that each generation knew its place in the community’s history.

The Eitzen name became a fixed surname in 1811, under the Napoleonic Code, which mandated hereditary family names across the Netherlands to standardize civil records. Before this, Frisian names were fluid—someone might be Jan Eitzen in one generation and Jan Pieterszen (son of Pieter) in the next, depending on their father’s name. When Napoleon’s reforms required families to choose a permanent surname, many Frisians, including the Eitzens, solidified their patronymic as a lasting family name. The choice of Eitzen, with its distinct -zen ending, preserved its Frisian character, distinguishing it from broader Dutch surnames like Jansen or Pietersen. This solidification ensured that the Eitzen name would carry its Frisian Mennonite identity through the family’s migrations to the Vistula Delta, the Russian Empire, and eventually to South America and Canada, serving as a testament to their origins in the marshy, windswept lands of Friesland.

The Ancient Frisii and the Saxon Repopulation of Friesland

The story of the Eitzen family begins in the marshy coastal lands of Friesland, a region shaped by the ancient Frisii, a Germanic tribe whose history stretches back to the 1st century BCE. The Frisii, as described by Roman writers like Tacitus, were a seafaring people living along the North Sea, from the Rhine Delta to the Ems River, in what is now the Netherlands and northern Germany. They were skilled in navigating the treacherous coastal waters, building artificial mounds called terpen to protect their villages from floods, and trading goods like amber and fish across the North Sea. Their independence and maritime culture defined them, but their encounter with the expanding Roman Empire in the 1st century CE would alter their trajectory.

The Romans, under generals like Drusus in 12 BCE, brought the Frisii into their orbit as a client tribe, demanding tribute in cattle hides and conscripting young men into auxiliary units. A revolt in 28 CE, sparked by oppressive taxation, briefly freed the Frisii, but Roman retaliation under Corbulo in 47 CE reasserted control. By the 3rd century, as Roman power waned, the Frisii faced mounting pressures—military campaigns, forced labor as serfs in Roman territories, and environmental challenges like rising sea levels. Archaeological evidence reveals a sharp decline in Frisian settlements during this period, with terpen sites like Wijnaldum-Tjitsma showing abandonment by the 4th century. While some Frisii were likely resettled by Romans in places like Gaul or Britain, small groups may have persisted in the region, their numbers drastically reduced.

Into this void came the Saxons, another Germanic people from modern Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony, during the Migration Period of the 4th to 6th centuries. As Roman authority collapsed, the Saxons, along with Angles and other tribes, moved into depopulated areas like Friesland, bringing with them their own customs, seen in artifacts like stamped pottery and new burial practices. These newcomers blended with any remaining Frisii, forming what historians call the “new Frisians” by the 6th century. This repopulated society retained the Frisian name—likely due to the region’s historical identity as Frisia—and spoke Old Frisian, a language closely related to Old English, reflecting their shared Ingvaeonic heritage. By the 7th century, these new Frisians had reestablished a distinct cultural identity, marked by maritime trade, communal governance, and resilience in a harsh coastal environment.

It was within this repopulated Frisian society that the Eitzen name likely took root. As a patronymic surname meaning “son of Eite,” Eitzen emerged among the farming families of medieval Friesland, reflecting the region’s tradition of naming that tied individuals to their paternal lineage. The Eitzens, like other Frisians, would have inherited the ancient Frisii’s adaptability and communal spirit, traits that would later define their Mennonite identity as they faced new challenges in the 16th century. The Saxon repopulation of Friesland, blending old Frisian elements with new Germanic influences, set the stage for the cultural and religious transformations that would shape the Eitzen family’s journey across continents.

Frisian Life Before and During the Rise of Mennonitism

By the medieval period, the Frisians of Friesland, descendants of the Saxon-repopulated society, had forged a distinct identity rooted in their coastal homeland. From the 5th to the 15th centuries, they were a resilient people, adapting to the marshy, flood-prone landscape through innovations like terpen and dikes. Their economy blended agriculture—cultivating barley and rye, raising cattle—with maritime trade, as they navigated the North Sea to exchange goods like wool, fish, and cheese in ports from Novgorod to London. The Frisians’ independence, known as the “Frisian Freedom,” set them apart from feudal Europe; they governed through communal assemblies, resisting lords and nobles until the Counts of Holland began asserting control in the late 13th century. Religiously, they had transitioned from Germanic paganism to Catholicism by the 11th century, with monasteries dotting the landscape, though their skepticism of centralized authority often put them at odds with the church.

The early 16th century brought seismic change to Friesland, as the Protestant Reformation swept through Europe. Martin Luther’s ideas reached the Netherlands by the 1520s, challenging Catholic doctrines and resonating with Frisians already wary of ecclesiastical power. Within this ferment, the Anabaptist movement emerged, advocating radical reforms like adult baptism and a return to New Testament simplicity. In Friesland, early Anabaptist leaders like Melchior Hoffman gained a following, but it was Menno Simons, a former Catholic priest from Witmarsum, who shaped the movement into a lasting tradition. After renouncing Catholicism in 1536, Menno organized the scattered Anabaptists into a peaceful, disciplined community, emphasizing nonviolence and communal living. His followers, soon called Mennonites, distinguished themselves from mainline Protestantism through core doctrines: adult baptism, symbolizing a voluntary commitment to faith; pacifism, rejecting all forms of violence; and separation from the world, prioritizing a distinct Christian community over secular engagement.

The Eitzen family, likely farmers in a Frisian town like Leeuwarden or Harlingen, would have been swept up in this religious upheaval. As a patronymic name meaning “son of Eite,” Eitzen was already embedded in Frisian tradition, reflecting the region’s emphasis on lineage and community. The Mennonite movement offered a spiritual framework that aligned with these values—congregational governance mirrored the Frisian Freedom’s communal assemblies, and the emphasis on mutual aid echoed the cooperative spirit of Frisian villages. Adopting Mennonite beliefs, however, came at a cost; the Catholic authorities and later Protestant rulers viewed Anabaptists as heretics, leading to persecution. The Eitzens, like many Frisian Mennonites, faced imprisonment, fines, or execution for their faith, prompting their eventual migration to the Vistula Delta in Prussia, where religious tolerance was promised. In embracing Mennonitism, the Eitzens not only preserved their Frisian identity but also set the course for a journey that would span continents, driven by their commitment to a faith born in the windswept lands of Friesland.

Migration to the Vistula Delta and Life in Prussia

The rise of Mennonitism in Friesland brought both spiritual renewal and severe persecution for families like the Eitzens. By the mid-16th century, the Dutch authorities, under pressure from the Catholic Habsburgs, intensified their crackdown on Anabaptists, viewing their rejection of infant baptism and refusal to swear oaths as threats to social order. Mennonites faced imprisonment, torture, and execution—over 1,500 Anabaptists were martyred in the Netherlands between 1531 and 1590, according to the Martyrs Mirror, a seminal Mennonite text. For the Eitzens, likely farmers in a Frisian town like Harlingen, the choice was stark: remain and risk death or seek refuge elsewhere. The Vistula Delta in Prussia, a region in modern northern Poland, offered a haven, as its rulers promised religious tolerance and economic opportunities.

The migration began in waves during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, with Mennonite families traveling overland through Germany or by sea along the Baltic coast. The Eitzens likely joined this exodus, settling in the Vistula Delta around places like Danzig (Gdańsk) or Elbing (Elbląg), where Mennonite communities thrived under the protection of Polish-Lithuanian nobles. The delta’s marshy landscape, reminiscent of Friesland, required skills the Eitzens already possessed—building dikes, draining wetlands, and constructing windmills for water management and milling. Their expertise transformed the region into fertile farmland, earning them favor with local authorities. Historical records note Mennonite contributions to the delta’s infrastructure, such as the arcaded windmills that became a hallmark of their settlements, reflecting the Frisian techniques they brought with them.

Life in the Vistula Delta was centered on faith and community. The Eitzens maintained their Mennonite doctrines—adult baptism, pacifism, and separation from the world—establishing self-governing congregations with their own schools and churches. They spoke Low German (Plautdietsch), a dialect rooted in their Frisian heritage, and upheld traditions of mutual aid, such as communal barn raisings and support for the poor. While they integrated economically, trading grain and dairy with Polish neighbors, they remained culturally distinct, avoiding intermarriage with outsiders and refraining from secular politics. This balance of adaptation and separation allowed the Eitzens to preserve their Frisian Mennonite identity, even as they prospered in Prussia for nearly two centuries. However, by the late 18th century, new pressures—Prussian restrictions on land ownership and military conscription—would push the Eitzens to seek a new home in the Russian Empire, continuing their journey of faith and resilience.

Settlement in the Russian Empire

By the late 18th century, the Eitzens and other Mennonites in the Vistula Delta faced growing challenges under Prussian rule. Restrictions on land ownership for non-Lutherans and pressures to serve in the military—contrary to their pacifist beliefs—threatened their way of life. In 1786, a lifeline emerged from the Russian Empire under Catherine the Great, a German-born empress eager to develop the newly acquired territories of New Russia (modern Ukraine) following the Russo-Turkish War. Catherine issued a manifesto offering German settlers, including Mennonites, generous incentives: 65 dessiatins (about 175 acres) of land per family, religious freedom, exemption from military service, and a 10-year tax break. These promises were a beacon for the Eitzens, aligning with their need for land, autonomy, and the freedom to practice their faith unhindered.

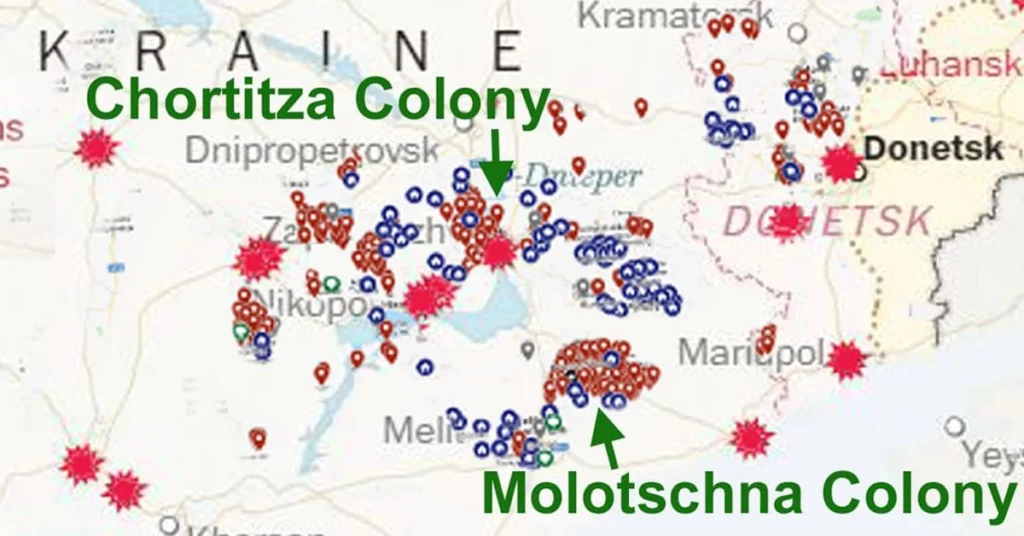

The Mennonites answered Catherine’s call with determination, seeing the opportunity to build a new life while preserving their beliefs. In 1788, representatives like Johann Bartsch and Jacob Höppner traveled to the region to scout land, negotiating with Russian officials to secure favorable terms. The following year, in 1789, the first wave of 228 Mennonite families, including the Eitzens, left the Vistula Delta for the Russian Empire’s Taurida Governorate. They journeyed overland through Poland and Ukraine, enduring a grueling trek to reach their new home near the Dnieper River, where they founded the Chortitza Colony, the first Mennonite settlement in Russia. The Eitzens settled in Schoenwiese, a village on the east bank of the Dnieper, just north of Alexandrovsk (modern Zaporizhzhia), where they established roots that would last for over a century.

Life in Chortitza was both challenging and rewarding for the Eitzens. The fertile steppes offered abundant land for farming, and the Mennonites quickly adapted their Frisian skills—building dikes, windmills, and communal villages—to the new environment. They grew wheat, barley, and oats, and raised livestock, contributing to the region’s agricultural prosperity. A record from the Odessa Archives (Fund 6, Inventory 1, File 43) places Daniel Von Eitzen in Schoenwiese around 1800–1812, where he joined other community leaders in petitioning about funds for the elderly, indicating his role as a respected member of the colony. The Eitzens upheld their Mennonite doctrines, maintaining self-governing congregations, speaking Low German (Plautdietsch), and practicing mutual aid through shared labor and resources. The Chortitza Colony became a testament to the Eitzens’ resilience and faith, but as the 19th century progressed, new pressures would once again set them on a path of migration, this time within the Russian Empire and beyond.

Expansion to Molotschna and Further Challenges

The success of the Chortitza Colony soon led to challenges for families like the Eitzens, as the growing population strained the available land. By the early 19th century, the Russian Empire continued to encourage Mennonite settlement, offering new opportunities further south. In 1803, a second wave of Mennonites from the Vistula Delta, along with some from Chortitza, responded to this call, establishing the Molotschna Colony in 1804, near modern Melitopol, Ukraine. The Eitzens likely had relatives among those who moved to Molotschna, as historical records like the 1835 Molotschna census note frequent transfers between the two colonies. Molotschna offered more land—over 120,000 dessiatins (about 324,000 acres)—and by 1820, it had grown to include around 1,200 families, becoming a thriving center of Mennonite life.

In Molotschna, the Eitzens and other Mennonites continued their agrarian traditions, cultivating crops and raising livestock on the expansive steppes. They built communal villages with shared resources, maintaining their self-governing congregations and educational systems. The colony’s administrative center, Halbstadt, became a hub for Mennonite governance, with elected leaders overseeing land distribution and community welfare. The Eitzens’ Frisian heritage remained evident in their use of Low German (Plautdietsch) and their architectural practices, such as constructing windmills for milling, a skill they had honed in Friesland and the Vistula Delta. Their Mennonite faith guided daily life, with a focus on mutual aid, pacifism, and separation from secular influences, ensuring cultural continuity despite the new environment.

However, the 19th century brought increasing challenges for the Eitzens in the Russian Empire. By the 1860s, Russification policies under Tsar Alexander II began to erode the privileges granted by Catherine the Great. The exemption from military service, a cornerstone of Mennonite life, was threatened as the Russian government sought to integrate all subjects into a unified national identity. Land shortages also intensified, as the Mennonite population grew and the best farmland was already claimed. Some families, potentially including Eitzen descendants, moved to daughter colonies like Bergthal (1836) or Fürstenland (1864), seeking new opportunities. These pressures foreshadowed greater upheavals in the early 20th century, as political instability, war, and revolution would ultimately drive the Eitzens and other Mennonites to seek refuge continuing their centuries-long journey of faith and adaptation.

20th-Century Diaspora to the East

The early 20th century unleashed unprecedented turmoil on the Mennonite colonies in the Russian Empire, forcing families like the Eitzens into a desperate struggle for survival. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, followed by the Russian Civil War, shattered the stability of Chortitza and Molotschna, as Mennonite communities faced violence, famine, and land confiscation. Stalin’s rise in the 1920s brought even harsher measures—collectivization stripped farmers of their land, and religious persecution targeted their pacifist beliefs, often leading to imprisonment or exile to labor camps in Siberia. For the Eitzens, whose roots in Schoenwiese traced back to Daniel Von Eitzen in 1800, remaining in Ukraine became increasingly perilous, prompting a daring journey across Russia to China in search of a safe haven.

Among those caught in this upheaval were my grandparents, Jakob Eitzen and Maria Wiens, whose lives intersected during this chaotic period. Jakob was born on January 15, 1913, in Leonidovka, Ignatyevo, South Russia, to Maria Siemens, age 24, and Jakob Eitzen, age 28, a family rooted in the Mennonite traditions of the Molotschna Colony. Maria was born on March 1, 1913, in Siberi, Karelia, Russia—a region far north of the Mennonite colonies—to Elisabeth (Liese) Friesen, age 31, and Jacob Isaak Wiens, age 33. Given Maria’s birthplace, it’s unlikely she met Jakob in Molotschna as a child, though their families likely crossed paths during the mass migrations of the late 1920s, as Mennonites from across Russia sought safety amid Stalin’s purges. By their mid-teens, both Jakob and Maria joined thousands of Mennonites fleeing eastward, embarking on a grueling trek across Russia that spanned over 3,000 miles. This journey, often undertaken on foot, by cart, or via overcrowded trains when available, took them through the Ural Mountains and the Siberian wilderness, enduring harsh winters, food scarcity, and the constant threat of bandits or Soviet authorities.

Their destination was Harbin, Heilongjiang, China, a city that had become a refuge for Mennonites and other Europeans fleeing persecution in the Soviet Union. Harbin, a cosmopolitan hub in the early 20th century, was shaped by its role as a key stop on the Chinese Eastern Railway and attracted a diverse population of exiles under the governance of the Republic of China and later Japanese occupation. For Jakob and Maria, Harbin offered a temporary sanctuary where they could practice their faith without immediate fear. On February 14, 1932, Jakob and Maria, both 18 years old, married in Harbin, a union that marked a moment of hope amid uncertainty. Life in Harbin contrasted sharply with their rural upbringing; the city was a bustling center with markets, churches, and schools, where Mennonite communities established congregations and maintained their Low German (Plautdietsch) language. Jakob likely worked as a laborer or craftsman, drawing on the practical skills of his Frisian Mennonite heritage, while Maria contributed through communal roles, supporting the tight-knit Mennonite network.

Their stay in Harbin was brief but pivotal. Just two weeks after their marriage, on February 28, 1932, Jakob and Maria joined a group of 80 Mennonite families departing Harbin by train to the coast, likely to a port city like Dalian or Tianjin. From there, they traveled to Shanghai, where they boarded a French passenger liner bound for Marseille, France. The Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), which organized the journey, had limited funds, so the group traveled in steerage—the cheapest class—crowded into the lower decks with minimal comforts for the weeks-long voyage across the Indian Ocean, through the Suez Canal, and into the Mediterranean. The MCC expected the passengers to repay the cost of their passage once settled, a burden that underscored the group’s determination to find a new home. Upon arriving in Marseille, they took a train north to Le Havre, where they boarded another liner for Buenos Aires, Argentina, continuing their journey across the Atlantic. From Buenos Aires, they traveled by river ship 1,500 km north to Puerto Casado, Paraguay, a week-long trip along the Paraguay River. At Puerto Casado, they disembarked and took a narrow-gauge train 145 km into the interior of the Chaco, a remote and arid region. At kilometer 145, settlers from Colonia Menno—established five years earlier in 1927 by Mennonites from Canada—awaited with ox carts, transporting the group another 100 km to a clearing in Colonia Fernheim, where they arrived on May 14, 1932. This arduous journey, spanning three continents and multiple modes of transport, showcased the resilience and communal spirit that had sustained the Eitzens through centuries of migration.

Building a New Life in Colonia Fernheim, Paraguay

Other Notable Locations with the Eitzen Name

Eitzen, Minnesota

Nestled in Houston County, Minnesota, near the border with Iowa, Eitzen is a small city with a population of 268 as of 2025, according to recent estimates. Founded in the mid-19th century, Eitzen, Minnesota, traces its name to early settlers from Eitzen, Germany, who arrived in the area seeking new opportunities in the American Midwest. The town’s history began taking shape in the 1850s, with the first German settlers, John and Jacob Meyer, arriving in 1853, followed by others who established a tight-knit farming community. By 1868, a post office was established, and the name Eitzen was chosen in honor of the settlers’ hometown in Germany, a connection solidified when Christian Bunge Jr., an immigrant from Eitzen, Germany, became the first postmaster.

Eitzen, Minnesota, embodies the rural charm of the Midwest, surrounded by rolling fields and family farms. Its history is deeply rooted in agriculture, baseball, and community traditions, such as the annual Eitzen Family Fun Fest held every July 4th. The Eitzen Community Center, built in 1955, remains a hub for local events, while the Eitzen Museum, housed in the old Christian Bunge Jr. Store—a stone building listed on the National Register of Historic Places—preserves artifacts of the town’s past. Though not directly connected to my Frisian Mennonite lineage, Eitzen, Minnesota, reflects a parallel story of migration and community-building, highlighting how the Eitzen name found a foothold in North America through determination and a shared cultural heritage.

Eitzen, Germany

The origin of the Eitzen name in Minnesota—and potentially a broader connection to families like mine—leads back to Eitzen, Germany, specifically the villages of Eitzen Eins and Eitzen Zwei in Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen). These small hamlets, part of the Uelzen district, are located in a region with a long history of Germanic settlement, dating back to the medieval period. Eitzen Eins and Eitzen Zwei, whose names translate to “Eitzen One” and “Eitzen Two,” are distinct but neighboring villages, likely differentiated for administrative purposes in centuries past. While specific historical records about these villages are scarce, their significance lies in their role as the ancestral home of settlers like Christian Bunge Jr., who brought the Eitzen name to Minnesota in the 19th century.

Lower Saxony, where Eitzen Eins and Eitzen Zwei are located, is a region of 7,890 cities and towns, with Eitzen Eins ranked as the 1,887th largest by population, indicating its small size. The area is characterized by its rural landscape, with a history of agriculture and trade, much like the Frisian lands where my ancestors originated. While my Eitzen family hails from Friesland, not Lower Saxony, the proximity of these regions in Northern Germany suggests a possible shared cultural or linguistic heritage, as both areas were inhabited by Germanic peoples with similar naming traditions. The Eitzen name in Germany, tied to these villages, underscores the deep roots of the surname in Northern Europe, a foundation that influenced its spread across the globe.

Other Eitzen Locations

Beyond Eitzen, Minnesota, and Eitzen, Germany, there are few other locations explicitly named Eitzen, suggesting the name’s geographical footprint is relatively limited. While the Eitzen surname appears in various parts of the world—carried by families like mine to places like Paraguay, Canada, and beyond—no other towns or cities prominently bear the name. It’s possible that smaller hamlets, streets, or historical sites named Eitzen exist, particularly in regions with German diaspora communities, such as parts of the United States, Canada, or South America. However, these are not well-documented, and the name’s most notable geographical markers remain tied to Minnesota and Lower Saxony. The scarcity of other Eitzen-named locations highlights the unique legacy of the surname, often carried forward by families rather than places, as seen in the journey of my own ancestors from Friesland to the Chaco.

Eitzen Chemical Company and Its Roots

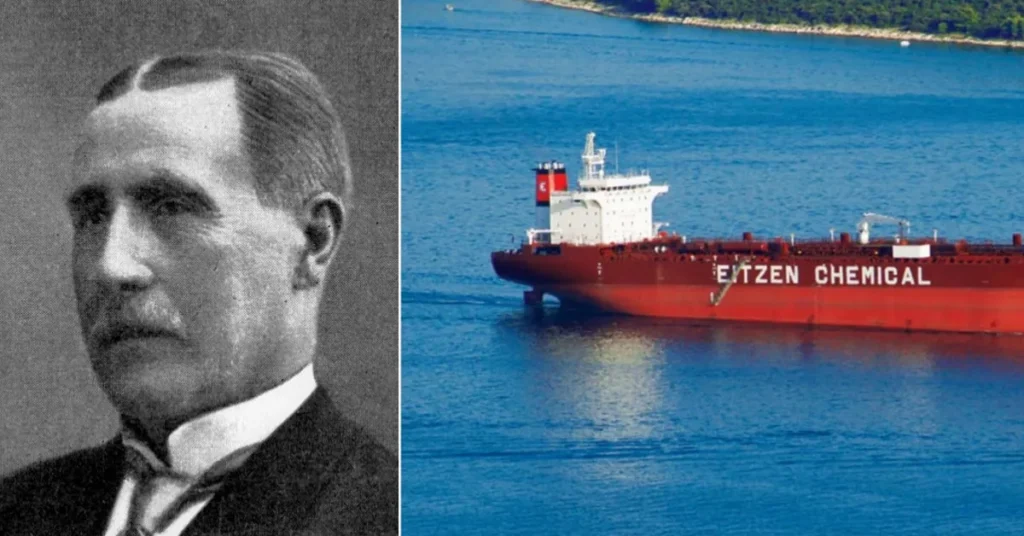

In Norway, the Eitzen name is prominently tied to the Eitzen Chemical Company, a maritime enterprise that traces its origins to Captain Camillo Eitzen, who founded Camillo Eitzen & Co. in Oslo in 1883. Born in Northern Germany—likely in a region like Schleswig-Holstein or Lower Saxony, close to the Frisian lands of my ancestors—Camillo Eitzen was a shipmaster who established a shipping business that would grow over 140 years into a global leader in maritime services. The company initially focused on general shipping but expanded significantly in 1894 when Captain Henri F. Tschudi became a partner, renaming the firm Tschudi & Eitzen. The purchase of their first steamship, S/S UTO, in 1895 marked the beginning of a long trajectory of growth, with the company entering the ore-bulk-oil carrier segment by 1967 and acquiring Danish company Skou International in 1990 to expand into bulk shipping.

The chemical transportation division, which would become Eitzen Chemical, emerged in 2001 when Tschudi & Eitzen acquired KIL Shipping A/S, a Danish company later renamed Camillo Eitzen (Denmark) A/S. This division grew through strategic acquisitions, including the French company Navale Française and the Spanish Naviera Quimica in 2004, and was de-merged into Eitzen Chemical in 2006, listing on the Oslo Stock Exchange that November. By 2007, Eitzen Chemical owned 72 vessels, commercially managed 12 more, and had 31 newbuilds, making it the third-largest chemical tanker operator globally by vessel count. The company specialized in transporting organic and non-organic chemicals, petroleum products, vegetable oils, and lubricants, operating across regions like the US, Europe, Asia, and South America. Despite financial challenges, including a significant loss in 2009 and a debt restructuring in 2011, the Eitzen family maintained control through Eitzen Holding AS. Eitzen Chemical was acquired by Team Tankers International in 2015, relocating its parent company to Bermuda, but the Eitzen Group continued its maritime legacy through subsidiaries like Christiania Shipping, which acquired 13 chemical tankers from Navquim in France in 2024.

The Norwegian Eitzens likely share a Northern German origin with my family, possibly descending from the same Frisian or Saxon roots in the medieval period. Unlike my ancestors, who embraced the Mennonite faith under Menno Simons in the 16th century, the Eitzens who founded this shipping dynasty may have prioritized maritime trade, establishing themselves in Oslo by the late 19th century. This divergence highlights the varied paths of the Eitzen name—while my family sought religious autonomy through migration, the Norwegian Eitzens built a commercial empire, carrying their Northern German heritage into the global maritime industry. Their story, rooted in Captain Camillo Eitzen’s vision, reflects a legacy of innovation and resilience, paralleling the communal strength that sustained my family through their migrations.

Frisian Roots or Saxon Soil? Weighing the Origins of the Eitzen Name

As with many old surnames, the origins of Eitzen are not without ambiguity. Today, the name appears in different regions and among diverse families—from small towns in North America to hamlets in Northern Germany. One commonly asked question is whether the name Eitzen derives from the Frisian patronymic tradition or from the village of Eitzen in Lower Saxony. While both theories hold historical merit, the evidence surrounding our family’s particular lineage points strongly to a Frisian origin.

The most compelling indicator is linguistic. Eitzen closely follows the patronymic naming patterns found in Friesland before the 19th century. In this system, surnames were fluid and often changed with each generation, identifying individuals by their father’s given name. In our case, Eitzen would mean “son of Eite,” with Eite being a traditional Frisian male name and -zen a regional suffix equivalent to the Dutch -sen. This is distinct from the standard German use of toponymic or occupational surnames, and the -zen suffix itself is rarely found outside the Frisian and Dutch-speaking parts of the Low Countries.

This naming tradition was solidified during the Napoleonic occupation of the Netherlands in 1811, when all families were required to adopt fixed surnames for civil record-keeping. Many Frisian families chose to preserve their patronymics, and Eitzen, with its clear reference to a paternal ancestor, would have been a natural choice. This practice was especially common among Mennonite communities in Friesland, who valued genealogy, oral history, and tight-knit familial identity.

In contrast, the villages of Eitzen Eins and Eitzen Zwei in Lower Saxony—while legitimate geographical names—likely gave rise to an entirely separate lineage of the Eitzen surname. Families originating from those places would have adopted Eitzen as a toponymic surname, meaning they or their ancestors came from that village. These families are often of Lutheran or Catholic background and typically followed very different migration paths from our own.

Our family’s journey—stretching from Friesland to the Vistula Delta, the steppes of southern Russia, and finally to the Chaco region of Paraguay—closely mirrors the established migration of Frisian Mennonites. The linguistic structure of the name, combined with this distinctive migratory pattern, makes a Frisian patronymic origin far more likely in our case. While the Eitzen villages of Lower Saxony share the name, they do not share the same cultural, religious, or linguistic context that shaped our family’s heritage.

In this way, the name Eitzen serves not just as a label, but as a living remnant of our Frisian Mennonite ancestry—a reminder of the values, beliefs, and resilient spirit carried across borders and generations. Though others may carry the same name for different reasons, the roots of our Eitzen family reach deeply into the windswept soils of Friesland, where identity was not simply inherited, but lived and shaped by faith, community, and migration.